My Signpost to the Past

As a way to celebrate Professor Thongchai Winichakul’s scholarly accomplishment, especially his most recent Grand Prize of Fukuoka Prize, I am pleased to introduce his seminal book, Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-body of a Nation, to our colleagues and friends of Letter from the Kamogawa River. I also want to take this opportunity to briefly point out how the book helps guide my research on Cambodia’s history.

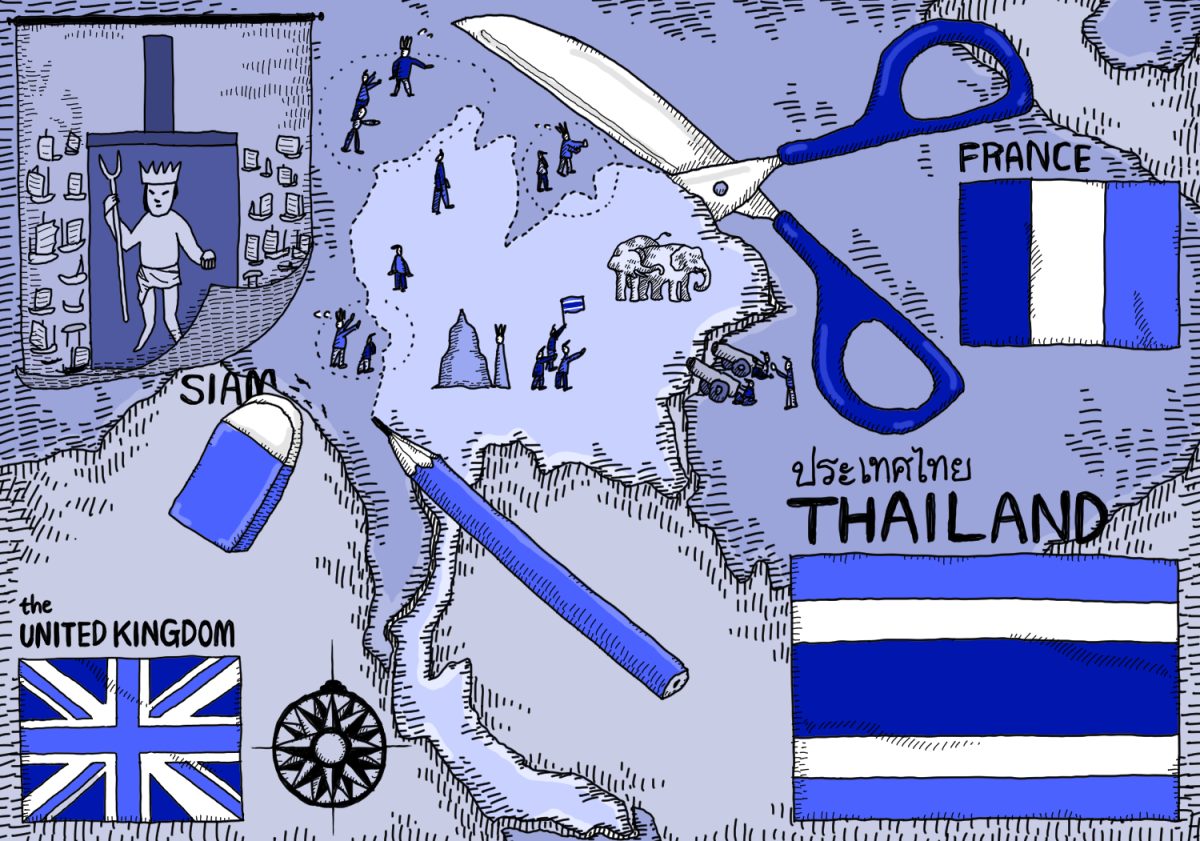

“Siam Mapped is never about map!” This is what Ajarn (meaning teacher in Thai) Thongchai told me when I asked for his autograph of my copy of the book in Singapore in July 2013. As a PhD student at the National University of Singapore at that time, I had a privilege to meet and discuss my dissertation project with him on multiple occasions. He said, Siam Mapped is a study of how a premodern state or polity had transformed into a modern nation which possesses a much stronger and broader collective understanding of nationhood. As the new technology of mapping introduced from the West was central to that transformation, the Siamese/Thai state had been placed under a new geographical discourse called “geo-body” which, consequently, transformed Siam into a fixed and distinctive nation-state both on maps and in collective consciousness of many Siamese people. Having realized this new understanding of national territoriality, Siamese ruling elites, mostly based in Bangkok, had to reinforce it either by launching military campaigns and state propaganda or through creating new national historical discourses that artificially conform Siam’s past with its new geo-body.

Having read Siam Mapped for many times, I have greatly benefited from the book in terms of its insights on Thai history and, more broadly, Southeast Asian history between the premodern and modern periods (roughly the 19th and mid-20th centuries). I am particularly amazed at Ajarn Thongchai’s creative way of exploring the long-held conceptions of indigenous territory and boundary, of which overlapping or multiple sovereignties were common across Southeast Asia. With the emergence of new mapping techniques, regional powers such as the Siamese state not only successfully utilized them to protect and strengthen their sovereignty against unprecedent threats of the French and British colonial powers. Their adaptation also caused to the disappearance of many small chiefdoms or polities, especially those located in the upper Mekong and Lao region. In this regard, the real losers of these new mapping techniques were those tiny and less power chiefdoms along the routes of both the Siamese and French forces (p. 129).

Thanks to Ajarn Thongchai’s pioneering scholarship, I have used a similar research framework to study the emergence of new ways of historical writing introduced from the West through Western colonial powers in Southeast Asia, especially Cambodia. Taking into account a wide range of indigenous scholarship, similar to mapping technology, the Cambodian educated elites were in great favour of the Western notion of history. However, their adaptation of this newly imported historical method happened in a more cautious and much less homogeneous manner because many indigenous scholars were quite conservative while others less so. Based on this phenomena I conclude that, unlike the new mapping techniques which had displaced the Southeast Asian indigenous notions of territory and boundary, Western historical writings never entirely wiped out the premodern indigenous history-making. In fact, under Western colonial conditions these two conceptions of history had played an interfacing role in creating new epistemological categories of historical scholarship in and of itself. My research will be published as a monograph, entitled Epistemology of the Past: Texts, History, and Intellectuals of Cambodia, 1850s-1970s, with the University of Hawai’i Press next year.