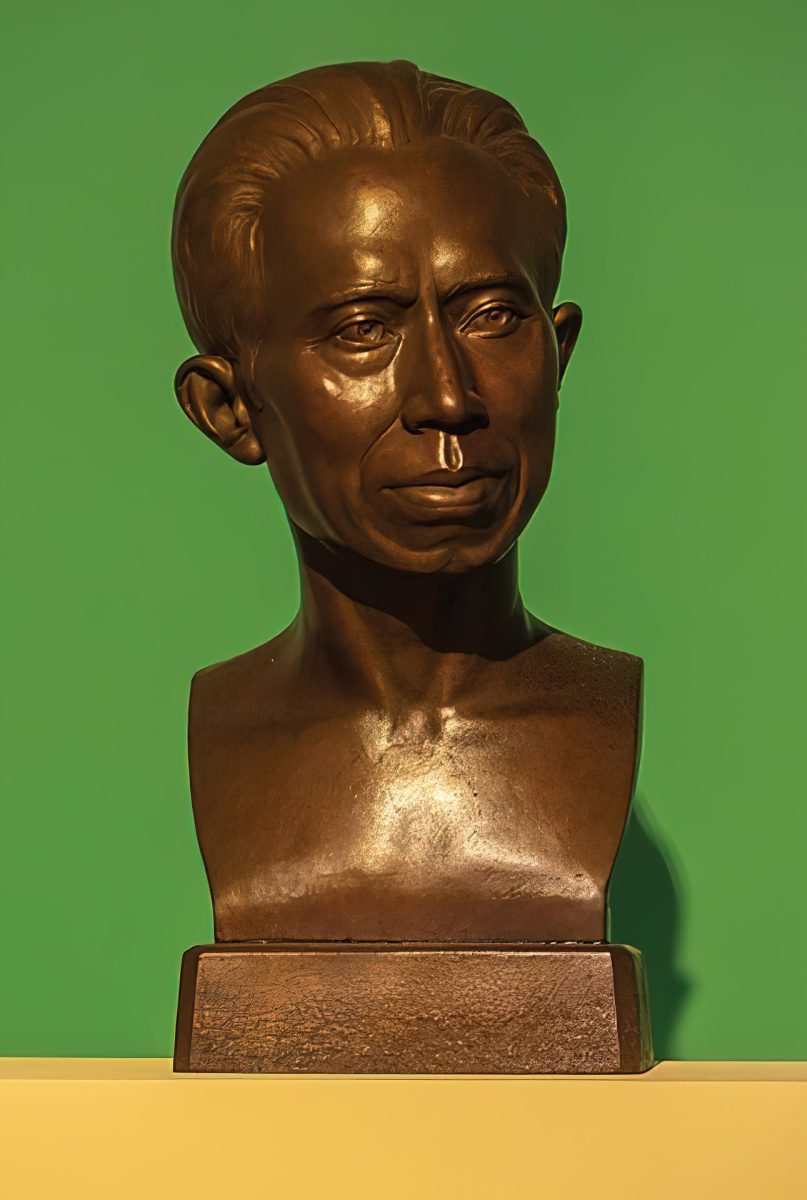

Chua, Lawrence

VISITOR’S VOICE

Interview with Lawrence Chua »

School of Architecture, Syracuse University

What are your favorite things?

Cinema

Before embarking on a PhD, I worked as a film critic and journalist. I realize now this was excellent training for understanding the ways narratives are constructed through fragments. The most meaningful movies to me are the ones that are narrated with very little dialogue. I am inspired by directors like Yasujiro Ozu, Fei Mu, Abbas Kiarostami, Julie Dash, and of course Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Anucha Boonyawatana.

Poetry

In another previous life, I was a novelist.[*] I never mastered writing poetry but I have always loved reading it. As a writer of prose, I am always inspired by the ways a good poet can create entire worlds out of very few words. I am also drawn to the discipline of poetic form and the rigor to which poets submit their creative imagination. I aspire to the same economy of language in my own writing.

Running

As a scholar who studies the history of cities and urban culture, running is not only a useful tool to clear one’s mind but also an insightful research method for exploring and understanding cities and how humans and other sentient beings inhabit them. I have loved running almost every morning along the Kamo river since I arrived in Kyoto.

[*] Chua, Lawrence. 1999. Gold by the inch: a novel. New York: Grove Press.

Photographer: Timothy Gerken

Interview

01

Please tell us about your research.

My first scholarly monograph, Bangkok Utopia examined architecture as a narrative form that made claims about modernity in a part of the world that has long been excluded from cultural histories of modernism.[1] My current project continues this exploration of the narrative qualities of the built environment by examining the ways disaggregated fragments of 9th– to 18th-century polities like Angkor, Sukhothai, and Ayutthaya “crossed over” from their older social and cosmological contexts into the progressive clock- and calendar-time of modernity.[2] Imperial and nationalist regimes used these fragments to produce a built landscape of uneven temporalities that supported teleological narratives whose apogee was the nation-state. However, these same fragments could also be understood as reminders of immiscible times[3] that never quite resolved into a uniform modern present and continue to haunt the built environments of Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos. They are also reminders of the ways Thai, Khmer, and Lao histories are entangled in ways that disrupt “purified” narratives of national heritage.[4] I think it’s important to understand the history of the built environment in which most of us operate because it is an ideological apparatus that filters reality in ways that we are rarely conscious of.[5] The project focuses mainly on sites, spaces, and cultures in and around the Tonle Sap, the Chao Phraya river basin, and the mountainous regions between the two. Chronologically, it is concerned with the 19th and 20th centuries and their view of the 9th through 18th centuries. Linguistically, it draws on Thai, Khmer, and French-language archives and inscriptions to offer a view of the entanglements of the “modern” and the “medieval” from the perspective of mainland Southeast Asia.

02

Can you share with us an episode about any influential people, things, and places you have encountered whilst doing your research?

After I had sent off the manuscript of Bangkok Utopia to the publisher, I visited Wat Rachathiwat วัดราชาธิวาส, a monastic complex on the Chao Phraya River in the north of Bangkok. Classified as a second-class royal temple, it was originally called Wat Samorai วัดสมอราย or Wat Samo วัดสมอ, a Thai corruption of the Khmer word thmo ថ្ម or “stone.”[6] The complex was adjacent to a historic Khmer community in the area. It was an important site in the mid-19th century when King Mongkut began the Thammayut reformation of the sangha on a raft moored just beyond where the current uposot now stands. The uposot underwent a major renovation in the early 20th century when it was redesigned by Prince Narisara Nuvadtivongs, a son of King Mongkut and one of the most prolific Siamese designers of the 20th century. Part of Prince Naris’ renovations include a series of murals, painted by the Florentine artist Carlo Rigoli, depicting the Vessantara Jataka. One of the last ten of the jataka stories, the Vessantara Jataka is a moving story about the responsibilities of the monarchy that circulated widely in an era of tributary states and mandala polities.[7] These murals sit within a design that accommodates not only reworked Khmer idioms but also features of the Baroque-revival style that was taught in the Paris-based École des Beaux-Arts, the prototypical school of architecture, in the late 19th century. The renovation and the murals are themselves arresting, but understanding the historical context in which they were accomplished makes the place even more fascinating. The turn of the century was a critical moment in which new understandings of sovereignty threatened the older cosmological rationale for the monarchy’s legitimacy. Prince Naris’ design holds these multiple histories in tension within a modern framework. It suggests the ways designers like Prince Naris conceived of modernity on the basis of a more complex framework than simple binary oppositions between “the West” and “Southeast Asia.”

03

Do you have any essential reads (books) that you can recommend to younger people?

For young historians, I would recommend History’s Anthropology: The Death of William Gooch by Greg Dening, an elegant and provocative meditation on historiography and colonialism; The Many-Headed Hydra by Marcus Rediker and Peter Linebaugh, an inspiring example of “history from below”; Ways of Seeing by John Berger, an evocative re-working of Walter Benjamin’s essay on “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Mechanical Reproducibility”; Gora by Rabindranath Tagore, a thoughtful novel about modernity, colonialism, and religion; Hanya Yanagihara’s expansive speculative novel To Paradise; and Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson, a queer love story and “novel in verse” based on fragments of classical Greek poetry.

04

Why do you choose CSEAS, or what is your expectation here?

I have long been drawn to the rich lineage of Southeast Asian historians who have been supported by CSEAS at critical moments in their research trajectories and by the ways the Center has been a haven for critical scholarship in the region. Being in Kyoto has reminded me of the intellectually rich and historically problematic relations between Japan and Southeast Asia, particularly around the subject of modernity in Asia. I’ve been particularly inspired by Takeuchi Yoshimi’s post-World War II provocation to re-position Asia from a subject of Cold War-era area studies to a method of research and thinking.[8] His insights into the ways China and Japan wrestled differently with the question of modernity in the 20th century are particularly relevant today as the field seems once again embroiled in a new era of political tension between the US and China.

(June 2023)

Note

[1] Chua, Lawrence. 2021. Bangkok Utopia: Modern Architecture and Buddhist Felicities, 1910-1973. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

[2] Werner, Michael and Bénédicte Zimmerman. 2006. Histoire Croisée and the Challenge of Reflexivity. History and Theory 45: 1, 30-50. Benjamin, Walter. 1968. Theses on the Philosophy of History. Illuminations and Other Essays. New York: Schocken. Anderson, Benedict R.O’G. 1983. Imagined Communities. New York: Verso.

[3] Fuhrmann, Arnika. 2016. Ghostly Desires. Durham: Duke University Press; Lim, Bliss Cua. 2009. Translating Time: Cinema, the Fantastic, and Temporal Critique. Durham: Duke University Press. Duara, Prasenjit. 1996. Rescuing History from the Nation: Questioning Narratives of Modern China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[4] Chit Phumisak. 2002. Tamnan haeng nakhon wat (“History of Angkor Wat”). Bangkok: Ammarin. Denes, Alexandra. 2022. A Siamese Prince Journeys to Angkor: Encounters with a Shared Heritage. Journal of the Siam Society 110: 1.

[5] Althusser, Louis. 1970. Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. New York: Monthly Review Press.

[6] Chulalongkorn. 1908. Phra ratchaniphon ruang wat samorai an mi nam wa rachathiwat (“The royal writings on Wat Samorai also known as rachathiwat”). Bangkok: Bamrung nukkulkit.

[7] Jory, Patrick. 2016. Thailand’s Theory of Monarchy: The Vessantara Jataka and the idea of the Perfect Man. Albany: SUNY Press, 2016.

[8] Yoshimi, Takeuchi, translated by Richard Calichman. 2005. What Is Modernity?: Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi. New York: Columbia University Press.

Reference

Dening, Greg. 1988. History’s Anthropology: The Death of William Gooch. Lanham: University Press of America.

Berger, John. 2008. Ways of Seeing. London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books.

Tagore, Rabindranath and Radha Chakravarty. 2009. Gora. New Delhi: Penguin Books India.

Yanagihara, Hanya. 2022. To Paradise First ed. New York: Doubleday.

Carson, Anne. 2013. Autobiography of Red. New York: Random House US.

Lawrence Chua is a Visiting Research Scholar of CSEAS

from June – November 2023

Thank you for taking the time to read the Visitor’s Voice interview.

Your feedback is important to us, so please let us know what you think.