Staff Page / Staff directory

TSUCHIYA, Kisho

- Research Departments・Position

- Social Coexistence

Assistant Professor - Area

- Southeast Asian area studies, modern history, postcolonialism, Cold War, borderland studies

- Research Interests / Keywords

- Timor-Leste, Indonesia, the Philippines, Cold War, postcolonialism, decolonization, borderland

- Contact

- kishotsuchiya@cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp

TSUCHIYA, Kisho

Overview

I am a historian and Southeast Asian area studies scholar specializing in colonialism, the Cold War, race and ethnicity, social warfare, place and space, borderlands, identity politics, community formation, religious transformation, human-rights, and multi-culturalism. In my ongoing and future research, I anticipate delving more into studies of inter-Asian connections, gender, migration, infrastructure, and technology. In the entirety of my research so far, I have provided perspectives and contexts regarding relatively marginalized spaces concerning global/transnational problems.

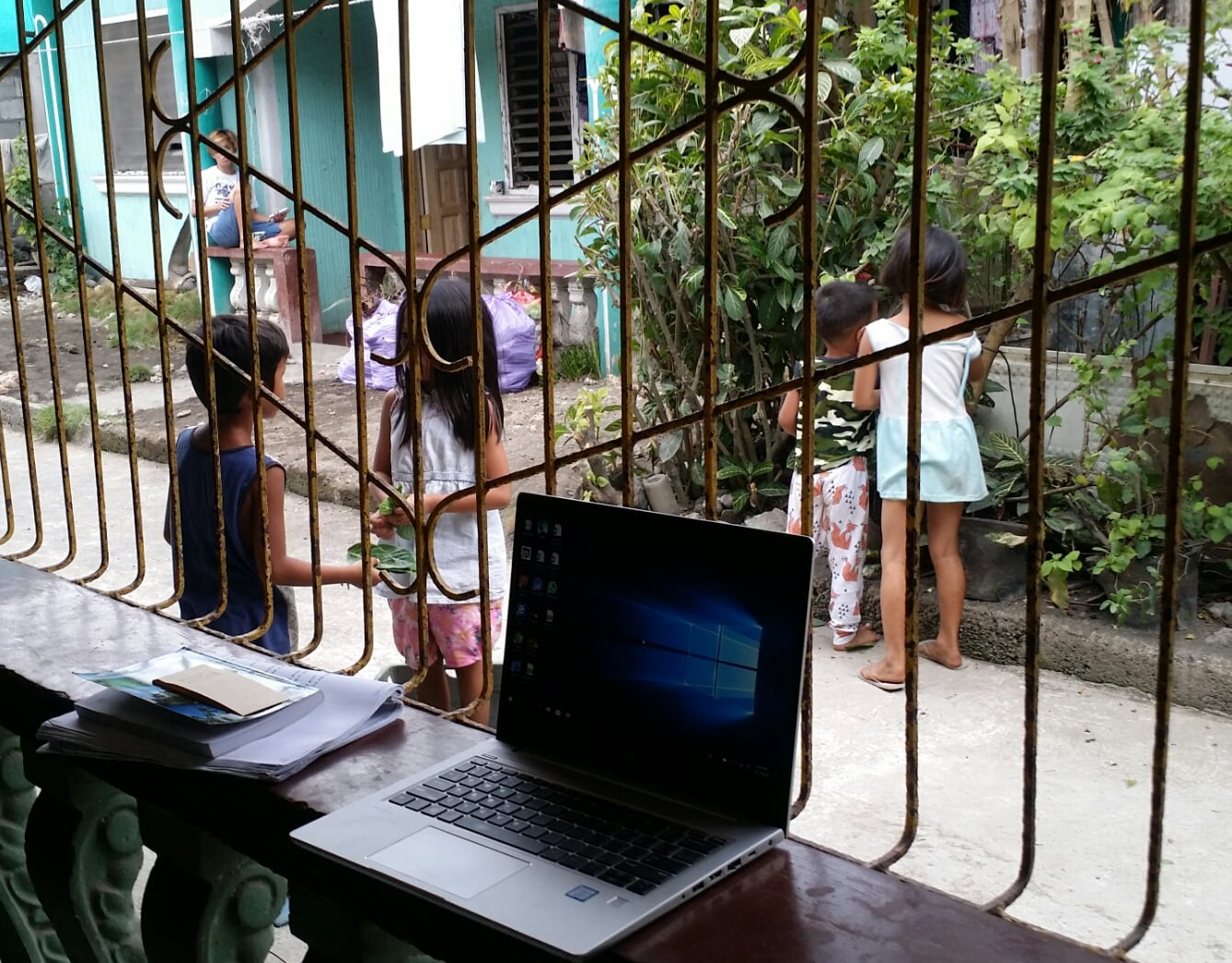

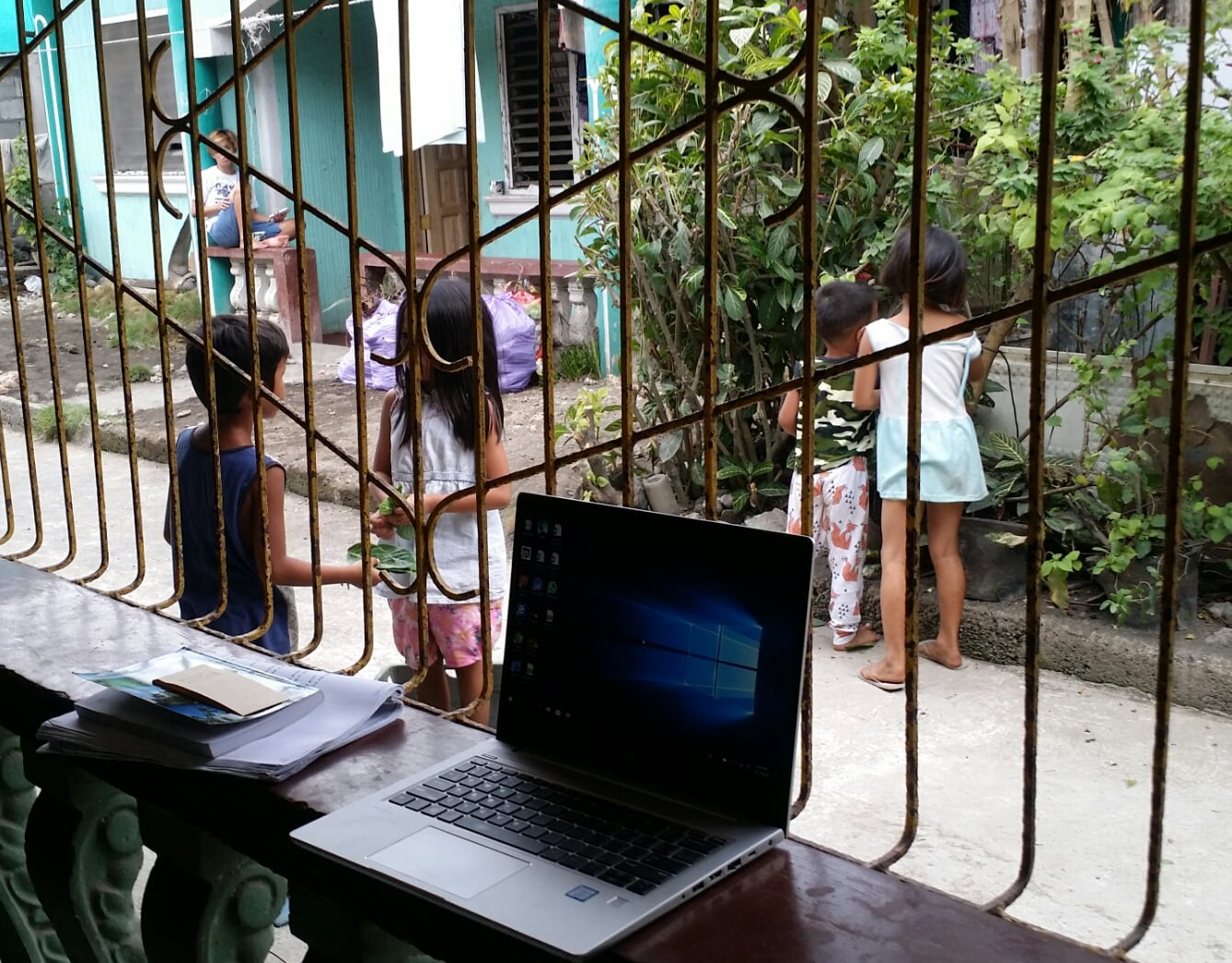

My fieldwork for the PhD dissertation focused on Timor-Leste and Indonesia since 2013. But, I also conducted archival research in Singapore, Portugal and Japan. More recently, I have been conducting fieldwork in Northern Mindanao in the Philippines, in addition to Timor-Island. Currently, I am collecting oral history interviews with various groups of people in order to reconstruct local experiences of the Cold War period from the perspectives of “ordinary people.”

My formal training was in history, Southeast Asian Studies, and international relations. Within the field of history, I focused on Asian history and topics such as historiography, social history, longue durée and the Cold War. During my graduate training, I was also exposed to disciplines such as cultural anthropology, sociology, political science, religious studies, and environmental studies.

My major research work can be categorized into two groups. One is the series of publications about the history of Timor Island which is currently divided by the international border between Indonesia and Timor-Leste. My research deals with how Timorese spaces and belonging have been ideationally imagined, physically made and practiced, politically and intellectually contested, and rhetorically justified as spaces of belonging. This research follows three main trajectories. The first offers a reminder of the ways in which political identity and resistance have been understood by international commentators. The second takes readers deeper into the past to demonstrate how notions of Timor were much more malleable and fluid, reflecting Southeast Asian and South Pacific ethnicities, politics and cultures, as well as colonial powers’ ideologies and practices. Finally, this research alerts the readers to the political role of emplacement by showing how different communities’ socially constructed understandings and physical spaces have reflected meanings, values, and worldviews that best suited their interests.

My second, and more recent fieldwork, archival research, and interviews deal with ordinary peoples’ experience of unCold Wars in Southeast Asia (1940s-90s), especially in the Philippines and Timor-Leste. Southeast Asia’s experience was characterized more by “hot wars”, conflicts, massacre, and social warfare (e.g. the Indonesian Red Purge, Khmer Rouge and the Indonesian occupation of East Timor) than a “Cold War.” Then, why Southeast Asians utilized the “Cold War” rhetoric to address their problems and to narrate their conflicts? In the coming years, I would like to understand what exactly the “(un)Cold War” was for the Southeast Asians.

My fieldwork for the PhD dissertation focused on Timor-Leste and Indonesia since 2013. But, I also conducted archival research in Singapore, Portugal and Japan. More recently, I have been conducting fieldwork in Northern Mindanao in the Philippines, in addition to Timor-Island. Currently, I am collecting oral history interviews with various groups of people in order to reconstruct local experiences of the Cold War period from the perspectives of “ordinary people.”

My formal training was in history, Southeast Asian Studies, and international relations. Within the field of history, I focused on Asian history and topics such as historiography, social history, longue durée and the Cold War. During my graduate training, I was also exposed to disciplines such as cultural anthropology, sociology, political science, religious studies, and environmental studies.

My major research work can be categorized into two groups. One is the series of publications about the history of Timor Island which is currently divided by the international border between Indonesia and Timor-Leste. My research deals with how Timorese spaces and belonging have been ideationally imagined, physically made and practiced, politically and intellectually contested, and rhetorically justified as spaces of belonging. This research follows three main trajectories. The first offers a reminder of the ways in which political identity and resistance have been understood by international commentators. The second takes readers deeper into the past to demonstrate how notions of Timor were much more malleable and fluid, reflecting Southeast Asian and South Pacific ethnicities, politics and cultures, as well as colonial powers’ ideologies and practices. Finally, this research alerts the readers to the political role of emplacement by showing how different communities’ socially constructed understandings and physical spaces have reflected meanings, values, and worldviews that best suited their interests.

My second, and more recent fieldwork, archival research, and interviews deal with ordinary peoples’ experience of unCold Wars in Southeast Asia (1940s-90s), especially in the Philippines and Timor-Leste. Southeast Asia’s experience was characterized more by “hot wars”, conflicts, massacre, and social warfare (e.g. the Indonesian Red Purge, Khmer Rouge and the Indonesian occupation of East Timor) than a “Cold War.” Then, why Southeast Asians utilized the “Cold War” rhetoric to address their problems and to narrate their conflicts? In the coming years, I would like to understand what exactly the “(un)Cold War” was for the Southeast Asians.