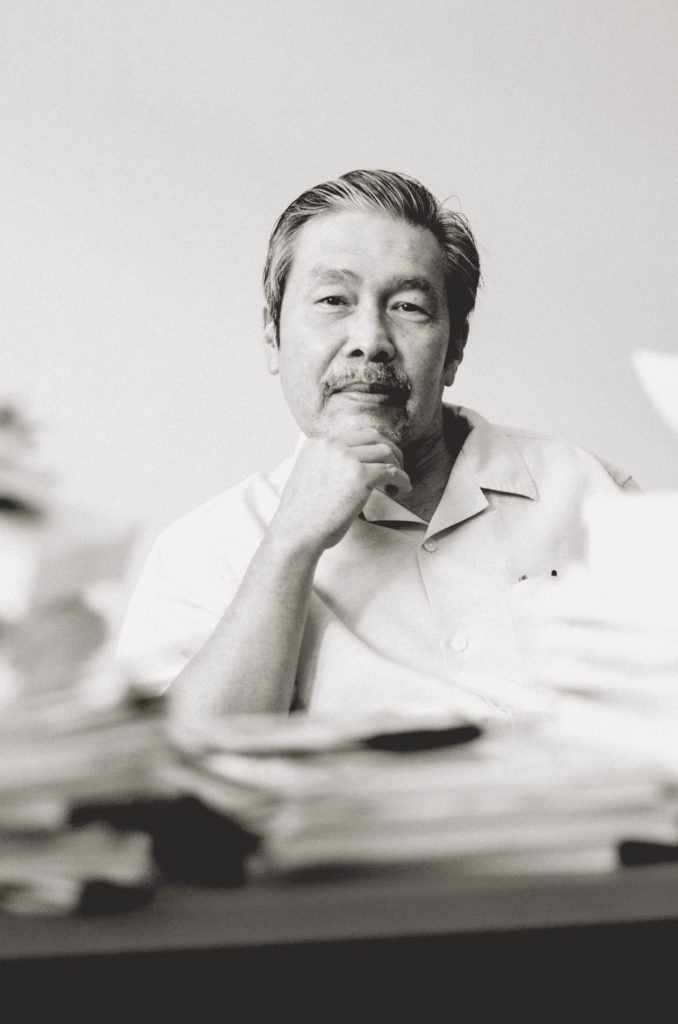

Santasombat, Yos

VISITOR’S VOICE

Interview with Yos Santasombat »

Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University

What are your favorite things?

✔ Food: Thai, Peranakan, and Japanese (not necessarily in this order)

✔ Musical instrument: I play classical guitar at home

✔ Hobbies: Reading books and watching movies

Interview

Applying an Ethnographic Approach to the Study of China’s BRI

01

Please tell us about your research.

My current research project is an attempt to assess and analyze the continuing impact of China’s rise, particularly the impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) megaprojects in Thailand and Southeast Asian countries, with a special focus on special economic zones (SEZs) and high-speed trains. Dr. Decha Tangseefa and I are currently editing the first monograph of this project, which is tentatively entitled China’s BRI in Southeast Asia: Concepts and Methodologies. This book argues that since its inception, the BRI has remained shrouded in confusion and controversy. The Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown of the past two years present additional challenges for our understanding of the BRI. Drawing insights from an extensive literature review and our ongoing empirical investigation of BRI projects in various Southeast Asian countries, this book is a conceptual and methodological experiment to map and analyze the dynamics and implications of China’s BRI, its growing international influence, and its economic development trajectory impacting socio-economic and cultural realities on the ground.

The comprehensive literature review shows that most of the existing academic studies on BRI are macro analyses, take a top-down approach, and are theoretical in nature. Few empirical studies are found that deal with BRI megaprojects and their relationship with local realities. Against this backdrop, we attempt to identify the potential impact of BRI on the development of ASEAN countries by way of conducting empirical research and case studies in various research sites to gain first-hand ethnographic data on the risks and benefits of the BRI projects at local, national, and regional levels.

The book is a collection of essays from a group of international researchers who share the conviction that China’s BRI and its impact on Southeast Asia should be examined through a variety of perspectives, such as transnational political economy, development studies, non-state centric, and geopolitical competition approaches. What differentiates our work is its ethnographic methodology, the qualitative process of exploring in-depth how people navigate the complexity of making and maintaining their lives in the context of socio-economic, political, and institutional changes brought about by BRI projects. Researchers immerse themselves in both quantitative and qualitative data from their inquiries and conduct iterative analysis to identify emerging issues and gain insight into the meaning and credible interpretation of the data.

Finally, our research reflects the concept of a cognitive injustice, or failure to recognize the different ways of knowing by which people across the region live their lives and provide meaning to their existence. Since the 15th century, Western colonialism has profoundly marginalized, overlooked, and erased local knowledge and wisdom in the Global South. Over the past decades, post-colonial scholars have outlined theoretical, methodological, and pedagogical frameworks for challenging the dominance of Eurocentric thought and deconstructing the Euro-American cognitive empire. Against this backdrop, we need to ask the following: Do BRI narratives focusing on transnational connectivity through infrastructure development, trade, investment, finance, energy, cultural exchange, and tourism in Eurasia and Africa constitute a reproduction of cognitive injustice? Is the BRI a Sinocentric cognitive empire marginalizing the epistemologies of the South?

02

How did you get started in your research and how did you come to focus on your current research?

I began pursuing the idea of doing fieldwork among the Tai ethnic minority in China forty years ago when I was a graduate student at Berkeley. But in the early 1980s, a graduate student from Stanford published an article in a Taiwanese newspaper on abortion practices in China and after that, it became increasingly difficult for students from American institutions to obtain permission to do field research in rural China. For me, then, China became a tempting destination left off the itinerary.

The prospects remained within me throughout the years, though, and when Professor Chatthip Nartsupha, head of the Tai History and Culture Studies Project, invited me to join him on a trip to Daikong, Yunnan in 1997, I readily accepted his invitation. In March of that year, I bid him goodbye in Kunming and took my family to Muang Khon in Daikong Prefecture to initiate my field research. The task I set for myself—indeed, the general theme that continues to sustain my study—is to discover how, over the last four centuries of Chinese domination, have the Tai groups in Daikong managed to maintain a strong sense of cultural continuity and ethnic identity.

03

Why do you find your research topic interesting?

I found fieldwork in Tai villages in Yunnan quite enjoyable and my book Lak Chang, an ethnography of a Tai minority in China, was written on the basis of my positive experiences. In the borderlands of China’s southwestern province of Yunnan, Tai farmers cultivate rice in irrigated paddy fields; exchange labor for transplanting and harvesting; refer to their fellow villagers as pi and nong (siblings); and unselfconsciously combine spiritualism with Theravada Buddhism. The local language is intelligible, though with some difficulty, to a Thai speaker. Little wonder that one important aspect of the renewal of cross-border linkages in the Thai–Yunnan region has been a growing interest—often imbued with nostalgia, a little fantasy, and the occasional dash of chauvinism—in the spatial and temporal continuities of Tai-ness. These various attempts to construct the distant past by studying the geographically distant respond nicely to a widely felt desire for cultural continuity in a space and time of economic, social, and environmental transformation.

Since the 1980s, continuous and sustained economic growth has given rise to a prosperous and powerful China. As one of the biggest markets and the second largest economy of the world, China has become an increasingly influential player in global and regional economic and political affairs. In Southeast Asia, China’s “charm offensive” is a catalyst for expanding and strengthening economic, cultural, political, and security linkages in order to maintain regional stability. This stability in turn preserves China’s economic growth and prominent regional leadership, facilitating increasing connectivity, access to resources and raw materials, and expansion into new markets. China’s rising power in the region is effectively disrupting the containment strategies employed by the United States during the Cold War era.

Since the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, China has been able to assuage fears that it poses an objective threat through economic cooperation (in the form of trade, investment, and foreign aid), regionalization, and global connectivity. China has taken advantage of the new regionalism becoming a skilled practitioner of “commercial diplomacy.” If China continues to lead the way in regional integration, (State-led) Chinese Capitalism will become integrated into the ASEAN Economic Community; this will be China’s essential strategy of “desecuritization.” Since 1997, I have turned my research attention to Chinese inroads into Southeast Asia, trying to understand the impact of China’s rise on Southeast Asia, the nature of Chinese Capitalism, the changing forms of Chinese Diaspora, and more recently, China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia.

04

Do you have any essential reads (books) that you can recommend to younger people?

I recommend Noam Chomsky’s Year 501: The Conquest Continues.

05

What is your ideal image of a researcher?

A scholar’s role is not for 40 hours a week or for sixty years. A scholar never retires. My future ambition is to never retire, but rather to keep on doing research and gradually fade away.

(March 2023)

Yos Santasombat is a Visiting Research Scholar of CSEAS

from March – August 2023