Dror, Olga

VISITOR’S VOICE

Interview with Olga Dror »

What are your favorite things?

Conversing with people

Nothing expands my horizons than talking with other people – friends, acquaintances, or complete strangers. Each person is a world in him/herself. These communications not only help me to discover their worlds but also to reflect on myself.

Travelling

It gives me so many new opportunities to converse not only with new people but also with new cultures (or rediscover the familiar ones). It is a miracle of an exposure to the human experiences in their geographical, geopolitical, cultural contexts.

Studying languages or exploring foods

I consider them as one item. Both help me to connect with the people and the places, both give enormous intellectual and physical satisfaction. What can be better to have an exquisite, even if simple, meal conversing with an interesting interlocutor in a language that you are studying?!

Archives, archives, and archives

It is such a thrill to open each new file in an archive and suddenly, abracadabra! you found something that completely changes your perception of your project.

Interview

Continuity, Changes, and Joys of Research:

Exploring Yourself

01

Please tell us about your research.

Born and raised in Leningrad in the USSR, I was educated there and later in Israel, where I emigrated in 1990, and in the United States. In the USA, I studied at Cornell University, where I focused on Sino-Vietnamese history in conjunction with literature and religion. I wrote a dissertation on Princess Lieu Hanh, a famous female deity in Vietnam who is often called a “Mother” of the Vietnamese people. Her cult originated in the sixteenth century and, in my study, I traced its development during different historical stages until the end of the twentieth century to demonstrate its relationship not only with ordinary followers but also with intellectuals and the state. In 2007, I published a monograph based on my dissertation.

While working in an archive in Paris, I discovered a treatise by an Italian missionary titled Opusculum de Sectis apud Sinenses et Tunkinenses (A Small Treatise on the Sects among the Chinese and Tonkinese) by Father Adriano di St. Thecla: A Study of Religion in China and North Vietnam in the Eighteenth Century, which is the first extant treatise about Vietnamese religions. Among other things, it discusses Princess Lieu Hanh and her cult as Adriano di St. Thecla found it in the eighteenth century. He claimed that Lieu Hanh was a prostitute. I decided to translate and annotate the Opusculum, written in Latin with parts in Chinese and Vietnamese, into English and to conduct a study to demonstrate that it was not the account of a dilettante, but of a person who had thoroughly studied his topic. The resultant volume (with M. Berezovska as a co-translator for Latin) was published in 2002, a year prior to the completion of my dissertation on Lieu Hanh in 2003.

Thus, my initial interest lay in theistic religions, but later it shifted to the modern period. Originating from the Soviet Union, a country that victoriously fought and suffered immensely in WWII, during which my grandparents and parents survived the siege of Leningrad, I have always been interested in the perspective of noncombatants in wars. While at Cornell, I learned about an account written by Nha Ca, a famous South Vietnamese writer. In 1969, she related her own experience and that of other civilians during the Tet Offensive in the city of Hue in 1968, including the massacre committed by the communist forces there. The work is still banned in Vietnam. In order to bring it to Western readers, I translated Nha Ca’s work and it was published in August 2014 as Mourning Headband for Hue. In addition to this very challenging translation, I wrote an extensive study of and introduction to the work, placing it in the historical context of the time.

My next project was a continuation of this interest. I wanted to better understand how it was for my parents to grow up during the time of WWII in a highly centralized and mobilized society that was fighting atrocious battles. By contrast, in the United States I witnessed the shaping of my own son’s identity in a very individualistic society. I saw the project as especially important to understand the position of children in the numerous current military conflicts around the world.

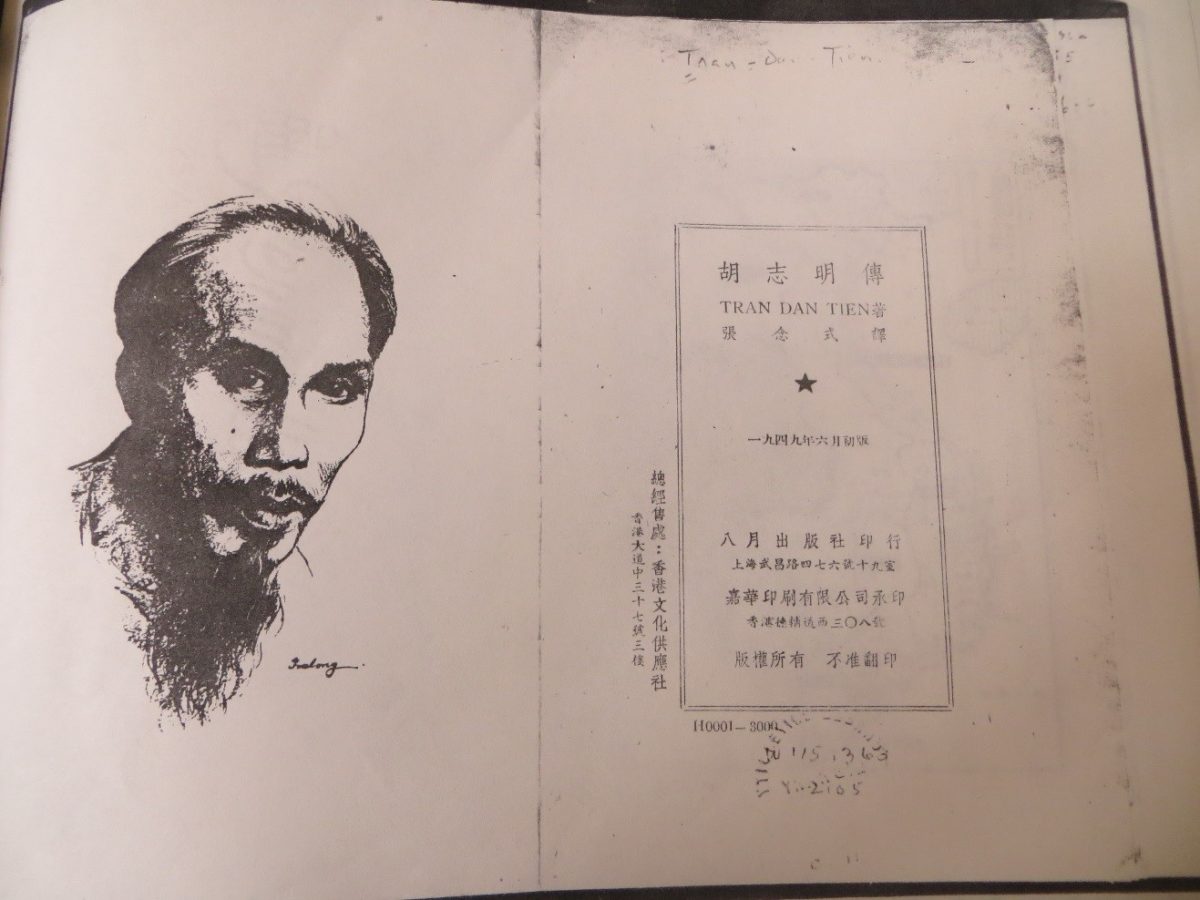

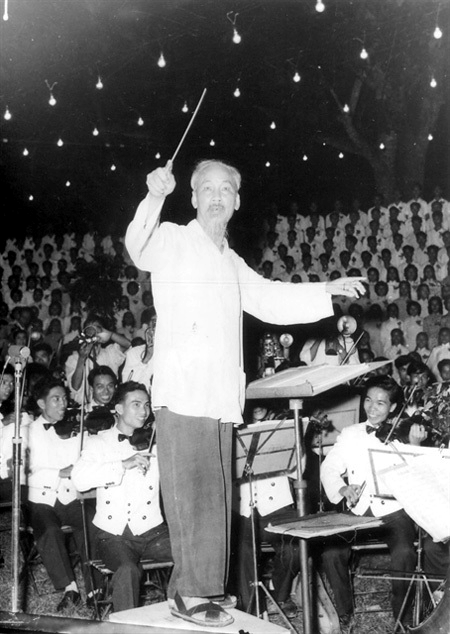

These issues captivated me, and made me move from studying non-combatants in Hue in 1968 to the ultimate non-combatants—children (or young people between the ages of 7 and 17). My project centered on shaping youth identities in North and South Vietnam during the war. In 2018, the Cambridge University Press published my book Making Two Vietnams: War and Youth Identities, 1965-1975. My current project brings together my interest in religion and in political culture. It focuses on the cult of Ho Chi Minh, the first president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, North Vietnam. His cult is a manifestation of political religion that replaced the theistic religion that I studied earlier. I first started to think about it while considering his role in the mobilization of communist youth during the war but then expanded it to the entire Vietnamese society and international communities. My book traces the origins of Ho Chi Minh’s cult and his own role in cementing his image not only as the leader of the nation but as the Uncle, the head of the Vietnamese national family. It also explores the development of the cult, the main personalities who contributed to it, and the different roles that his cult played and is playing in Vietnam and around the world.

02

Can you share with us an episode about any influential people, things, and places you have encountered whilst doing your research?

For me, practically each place and each person are influential. It’s up to us to open up to the new experiences.

03

How do you overcome the difficulties in putting together the results of your research into a research paper or book?

I overcome these difficulties with difficulty. I always have so much more material than I can squeeze into my writing pieces. What helps me is to create a narrative structure and to see where the materials lead me to create my thesis/argument.

04

Do you have any must-have gear for field research and writing?

Yes. Good humor, openness to new discoveries and new adventures.

05

What is your ideal image of a researcher, and do you have any advice for those who aim to become researchers?

One should become a researcher only if one loves research. Don’t become a researcher because you would like to become a professor. The job market vacillates and it is not always assured that you would find such a position. While it certainly depends on the quality of your work, the job market is also a gamble and a draw of luck. So, become a researcher for the sake of research! You will also discover that while you are researching a certain topic, you also change and discover new things about yourself.

06

What are your future ambitions as a scholar?

To work in the archives around the world, to meet people, to write books, AND to help young researchers enter the world.

(July 2023)

Olga Dror is a Visiting Research Scholar of CSEAS

from July 2023 – January 2024

Thank you for taking the time to read the Visitor’s Voice interview.

Your feedback is important to us, so please let us know what you think.