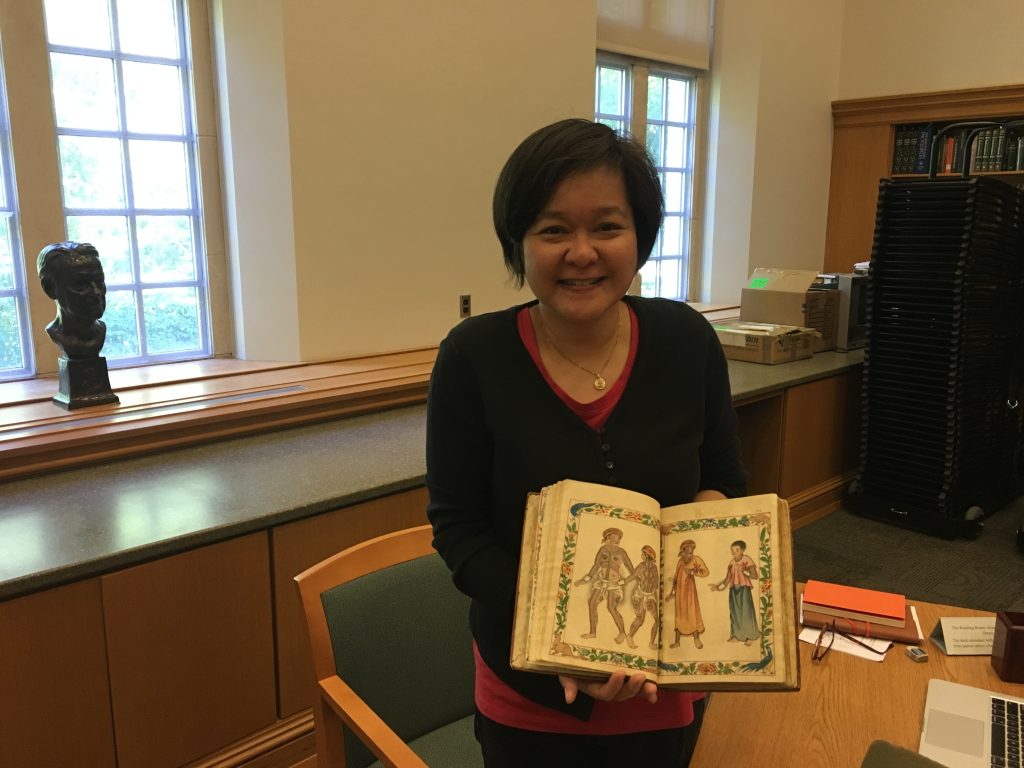

Patricia May Bantug Jurilla

VISITOR’S VOICE

Interview with Patricia May Bantug Jurilla

Writing Books about Books

Please tell us about your research.

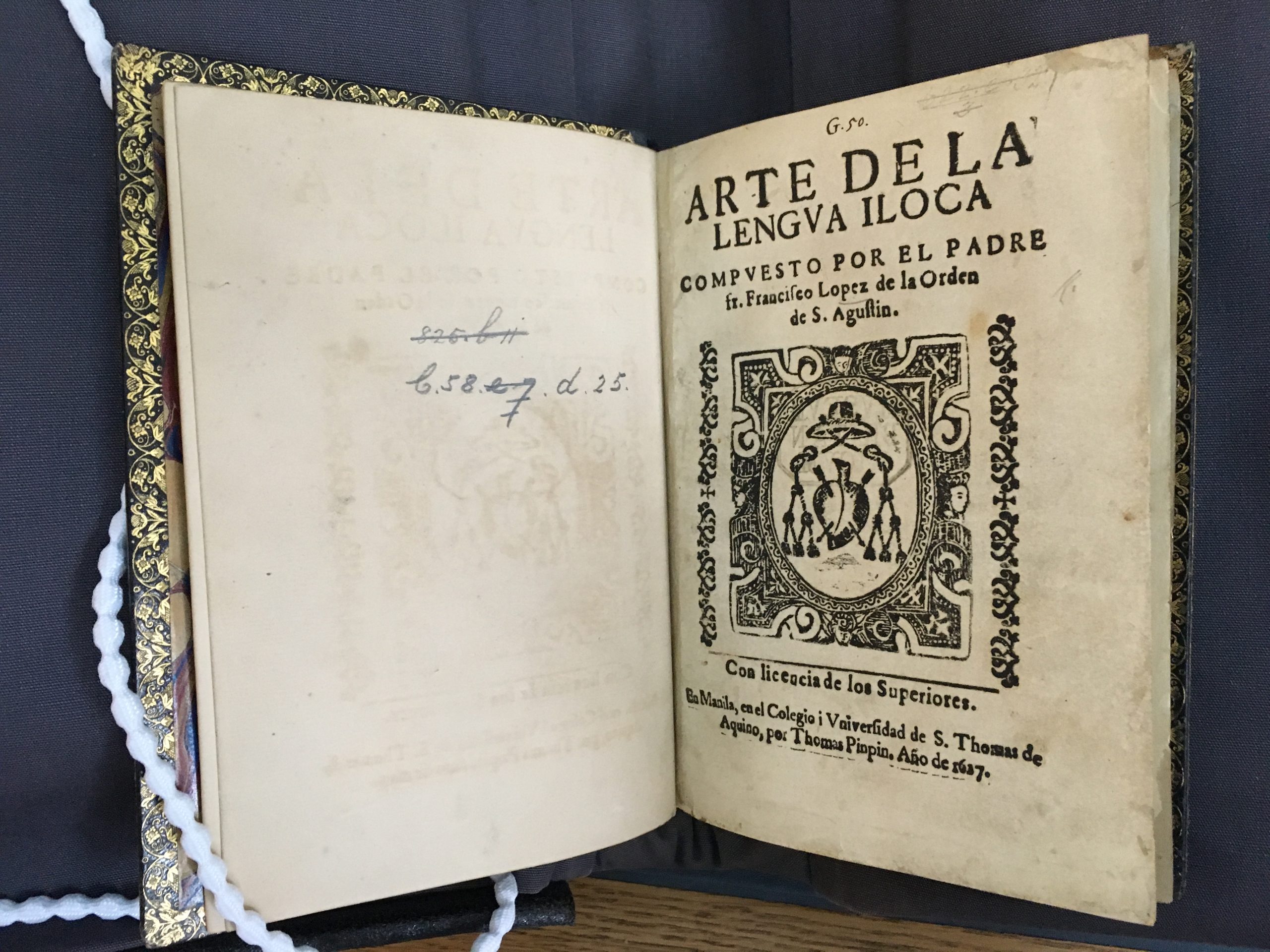

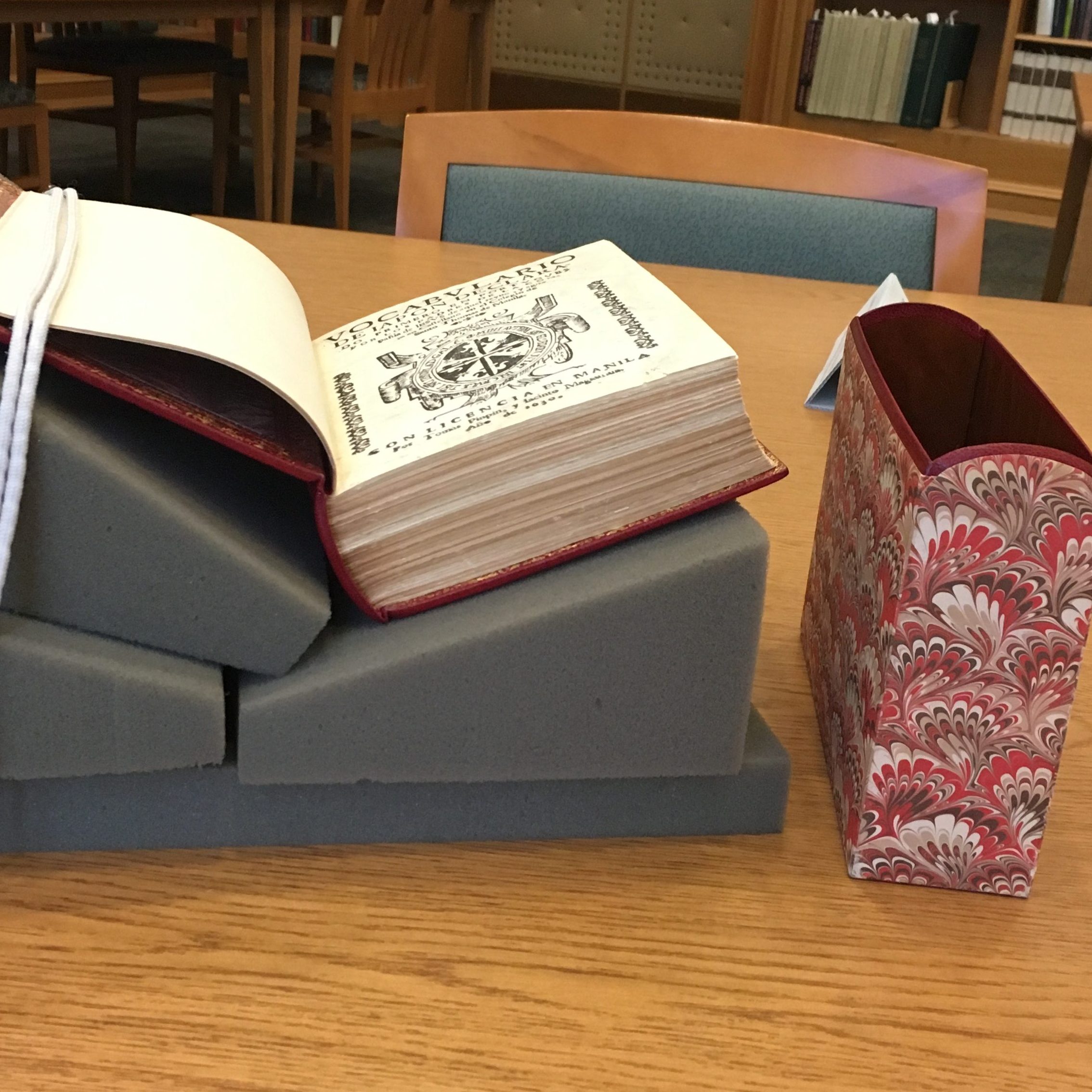

My research is on the survival of early Philippine books, an area that has not been given full attention in Philippine book history. I am conducting case studies on five books printed in Manila during the 17th century. In each case study (or for each book), I examine the book’s initial creation and reception, its dormant period, and its emergence as a rare book when it gained new importance among collectors and scholars. Through these studies, I hope to provide more information and insights on 17th-century publishing in the Philippines, the reception of books throughout the ages, and the culture of collecting in modern times. Ultimately, I aim to further the understanding of the survival of Philippine books in general and to contribute to Philippine historiography.

How many research themes do you have?

The main theme of my current research, which is the survival of books, naturally flows into other streams of study, such as book manufacturing and preservation, print culture, colonialism and post-colonialism, collection studies, and digital humanities.

My previous work on Philippine book history was on 20th-century literary publishing, Tagalog bestsellers, and the novel in the Philippines.

Why do you find your research topic interesting?

Books have stories to tell beyond their subjects and contents. Each stage in the life of a book—its authorship, publication, distribution, reception, and survival—involves many persons, interactions, and events that exist amid the social, cultural, and political currents of their time. Book histories uncover complex human stories and incidents that connect to culture and society. For example, the story of why a famous and prolific poet-playwright, nearing death, forbade his children from becoming writers, claiming that it would be better to have their hands cut off than to follow in his footsteps; or the story of how a self-published novelist borrowed money from friends and family and moved to a city where printing was cheaper, yet his books eventually inspired a national revolution; or the story of how one country’s presidential decree ignored all international copyright laws, making it quite unpopular with foreign publishers and authors. I am fascinated by stories of books because there is no lack of drama, comedy, and tragedy in them and because I learn so much from them about creativity, conviction, and, ultimately, the human condition.

How did you get started in your research and how did you come to focus on your current research?

I traveled a long route to arrive at book history. I started in journalism, but found that I was not suited to it. I then moved to literary studies, which I became competent enough in, but which I tired of at some point. Eventually, I found out via the Internet that there is this field called ‘the History of the Book.’ I quickly recognized that it was the best-of-both-worlds spot that I didn’t know I was looking for, the discipline where my training and experiences in journalism and literary studies could come together and where my desire to feel and smell books would not seem odd. I began with postgraduate studies in book history, reading and studying countless books in the process, and became a book historian.

My current research sprang from idly scouring the rare book catalogues of antiquarian booksellers and national libraries (mainly the British Library) for fun when I was in postgraduate school. While doing random searches on Philippine books, I would inevitably get to wondering: how in the world did these books get to where they are? Having exhausted the materials from my PhD work and being exhausted by its subject already, I wanted to work on something else and thought that I should finally address the question about the rare old books of the Philippines that had long baffled and fascinated me.

Have you had any difficulties in putting together the results of your research into a research paper or book?

Research and writing are never easy for me, but I immensely enjoy doing both, perhaps precisely because I find them challenging. In research, the most common obstacle I come across is the inaccessibility or unavailability of data. This is because records are not always made or preserved well in the Philippines and because Philippine books do not always survive all too well either. In writing, my process has a rhythm of its own, one that seems to defy all circadian patterns, so the difficulty for me is finding the time, place, and conditions conducive to letting this rhythm run freely and fully.

Which books or people have influenced you?

For my grounding in the History of the Book, the works of Robert Darnton, the model of Thomas R. Adams and Nicolas Barker, the lectures of D. F. McKenzie on the ‘sociology of texts,’ Jerome J. McGann’s critique of textual criticism, and Benedict Anderson’s concept of ‘imagined community.’

For my studies on Philippine book history, the bibliographies of Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, W. E. Retana, José Toribio Medina, and the works of Damiana L. Eugenio, Resil B. Mojares, Regalado Trota Jose, Vicente S. Hernández, and Ambeth R. Ocampo.

What is your ideal image of a researcher?

I imagine the ideal researcher, specifically one in the Humanities, to be constantly curious, courageous, and tireless in the search for truth; highly articulate in speaking and writing; compassionate and empathetic; and always honest and ethical. Also, one who thinks the world of one’s research area, but recognizes, is unfazed by, and does not resent that there happens to be a world outside of it that does not always understand or care.

What is your must-have gear for field research and writing?

MacBook Pro for research and writing, iPad for reading digital books and documents, iPhone for taking photos and scanning pages, tape measure, white cotton gloves (because some libraries still insist on the use of such for handling rare books when actually this should not be necessary anymore), a good old-fashioned analogue notebook, unruled index cards, pencils, and wet wipes.

What would you say to people who want to become researchers?

Go for it! Seek the truth through research, then tell it and protect it. And always be kind to your books.

What ambitions do you have for the future?

Mainly, to be able to write more books about books. Generally, to keep battling against historical revisionism, negation, and ignorance, especially in the Philippines.

(September 2022)

References

Adams, Thomas R. and Nicolas Barker. 2001. A New Model for the Study of the Book. In A Potencie of Life: Books in Society, edited by Nicolas Barker, pp. 5–43. London: British Library; New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press.

Anderson, Benedict. 1981. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, revised ed. London and New York: Verso.

Darnton, Robert. 1982. “What Is the History of Books?” Daedalus 111 (3): 65–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024803.

Eugenio, Damiana L. 1987. Awit and Corrido: Philippine Metrical Romances. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Hernández, Vicente S. 1996. History of Books and Libraries in the Philippines 1521–1900. Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Jose, Regalado Trota. 1993. Impreso: Philippine Imprints 1593–1811. Makati: Fundación Santiago and Ayala Foundation.

McGann, Jerome J. 1983. A Critique of Modern Textual Criticism. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press. Reprint, Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 1992.

McKenzie, D. F. 1986. Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts. London: British Library. Reprint, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Medina, José Toribio. 1896. La imprenta en Manila desde sus origenes hasta 1810. Santiago de Chile: Impreso y grabado en casa del autor. Reprint, Amsterdam: N. Israel, 1964.

Mojares, Resil B. 1998. Origins and Rise of the Filipino Novel: A Generic Study of the Novel Until 1940, 2nd ed. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Ocampo, Ambeth R. 1990. Rizal Without the Overcoat, 2-3. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing.

Pardo de Tavera, Trinidad H. 1903. Biblioteca Filipina. In Bibliography of the Philippine Islands. Washington: Government Printing Office. Reprint, Manila: National Historical Institute, 1994.

Retana, W. E. 1911. Origenes de la imprenta en Filipinas. Madrid: Librería General de Victoriano Suárez.

Patricia May Bantug Jurilla is a Visiting Research Scholar of CSEAS

from August 2022 – January 2023